- ASTS Home

- Events

- Training

- Professional Development

-

Advocacy & Resources

- Advocacy Library

- Wellness Resources

- Trainee and Resident Resources

- Member Insurance Benefit

- Join the AMA

- ASTS Surveys

- Position Statements

- Surgical Standards

- NSQIP

- OPTN Modernization Initiative

- Statement of Policy Principles and Solutions Living Organ Donation

- Community Engagement

- SRTR Subway Map

- Patient Voice Initiative

- Photography and Documentation Standards for Recovered Organs

-

TAC

- TACC: Council and Committees

- Fellowship Training Programs

- Fellowship Requirements

- Fellowship Certification Pathway

- Career Certification Pathway

- Career Recognition Certification Pathway

- Program Accreditation

- Program Director Resources

- Match Information

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Fellowship in Transplantation Grant

- TAC Portal Fellows

- TAC Portal Programs

- Connect

Putting a Liver on Pump: The Pumper’s Perspective

Brendan P. Lovasik, MD and Jennifer Yu, MD

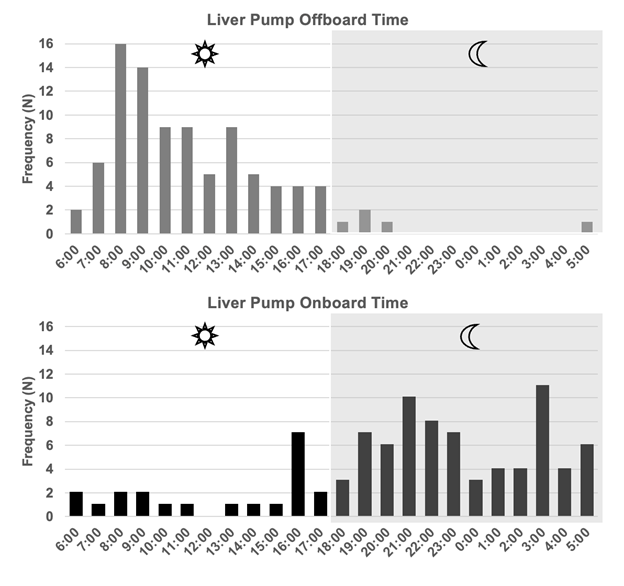

Normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) of liver allografts has rapidly changed the landscape of liver transplant and is a burgeoning area of growth in programs across the country. Transplant surgeons and the Chimera readership are certainly aware of the benefits of NMP technology. Perhaps most dramatically, NMP has been shown to extend traditional ex vivo preservation times – the average NMP duration in our series is 10hr48min. This has resulted in a significant shift in the time of day for the recipient operation, allowing surgeons to perform more transplants during conventional daylight hours, with advantages for patient safety and surgeon, anesthesiologist, and surgical staff quality of life. Of the livers that are pumped on the NMP device, WashU performs 95% of transplants during standard working hours (Panel A). NMP allows centers to accept more marginal organs, with the benefit of being able to perform viability testing of the liver on the pump prior to implanting in a patient – this is the primary goal of the RESTORE trial, which is led by WashU surgeon Dr. William Chapman. It also allows centers to accept more expanded criteria offers, including open offers, livers from donors after circulatory death (DCD) with pending serologies or biopsy results, regional imports, and late/intra-operative declines by other centers without requiring an in-house “backup” recipient. A robust NMP program also provides excellent opportunities for transplant centers to establish research programs in both basic and clinical science. The act of pumping a liver can be a highly beneficial educational opportunity for fellows to independently lead the liver backbench preparation, high hilar dissections, and complex arterial reconstructions for cannulation.

The preparation, cannulation, and onboarding of a liver for NMP is a significant personnel commitment – particularly for the “pumpers”. While donor call coverage may be shared among fellows and many attendings, the “pumpers” are usually a much smaller pool, consisting of fellows, junior faculty, and/or specially trained advanced practice providers or surgical technologists. This personnel commitment is compounded by the off-hours at which most of these liver procurements and subsequent liver pump onboardings continue to occur – in the WashU series, over 77% of pump onboardings occur during evening or overnight hours, with half of all onboardings occurring between 21:00 and 04:00 (Panel B). As demonstrated in the onboard/offboarding figures above, the vast majority of livers are associated with a range of afternoon or evening procurement times, with NMP then allowing for a “first start” OR time during standard working hours). Further, while the backtable preparation of a liver is typically a one-surgeon task, the cannulation of vessels and onboarding of the liver onto the NMP machine is much more efficiently performed by two surgeons working together (though on rare occasions, one surgeon and a resident/medical student have onboarded the liver, which takes significantly longer). The backtable preparation and onboarding for a single liver usually requires about 70 to 120 minutes from start to finish - this is largely determined by aberrant anatomy or the need for additional arterial reconstruction. This additional time can be demanding if the same surgeon / team that performed the organ procurement is also responsible for putting the liver on pump. At our institution, to the best of our ability, we try to arrange a separate team to pump the liver as a reprieve to the procuring team – this sometimes results in up to 6 surgeons being involved in a single liver transplant from procurement to pumping to implantation – this model obviously poses a burden to smaller transplant centers that may not have the surgeon personnel to supply this volume of staff. The onboarding procedure itself is complicated by the inability to use monopolar electrocautery or hemostatic agents, which adds to the overall procedure time as the majority of hemostasis efforts and repairs must be performed with suture. A physical lift for the OrganOx Metra device was also recently clinically approved for use; however, the functionality of the lift has yet to be fully realized due to implementation barriers – currently, liver onboarding typically required surgeons to kneel on the floor next to the device or sit on short stools to reach the low-situated basin containing the liver.

While NMP has multiple beneficial applications, it does add an additional step in which complications could occur. Cradle compression of the organ on the pump can generate significant pressure necrosis within the liver parenchyma, particularly for those grafts with sizeable, weighty right hemilivers, that can, at its worst, cause early allograft dysfunction and later lead to abscesses or even graft failure. Further, the cost of the NMP disposable or non-reusable materials, including the pump cassette, liver basin, and blood, cannot be discounted, though the increase in transplant rates and providing more livers for transplantation is considered to outweigh these costs on net balance. We have received some livers as imports with poor biopsy results or dissected/thrombosed vessels that we ultimately decided not to pump after backtable evaluation, though we had already opened the pump disposable materials in preparation; however, for each of these unacceptable organs, we have been able to rescue dozens of livers that would otherwise not have been utilized.

The pumps used by WashU are maintained and housed by our local organ procurement organization (OPO), and OPO staff assist in the setup and on-pump preservation of the organ. This is a very advantageous structure for our NMP program, as it provides a reliable and experienced OPO staff member to monitor the liver without having to employ/dedicate additional surgical staff for the maintenance of the pump. During a machine perfusion run, the OPO provides one recovery coordinator to prepare the pump and maintain the organ after onboarding, to run labs, to provide maintenance medication support, and to communicate with the accepting surgeon for the duration of the pump. The OPO also provides a surgical technician who sets up our backtable and our (lovingly named) “cannulation station”. The act of pumping an organ is a significant personnel and time commitment for the OPO, in an era where their staff are already working at maximum capacity. To ensure this model is a sustainable process, we are currently working on a quality-of-life study for all staff involved in liver transplants, from the donor, pump, and recipient sides, to see who is impacted by this new technology as we use it increasingly more often, and in what way their lives have been affected. We believe these perspectives can help us best implement collaborative practices for these new technologies in sustainable and cooperative ways.

Dr. Lovasik is a fellow in transplant surgery at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Yu is an Assistant Professor of Surgery at Washington University in St. Louis.

Panel A/B: Normothermic machine perfusion onboarding/offboarding times for liver transplants at WashU 2022-2024. 95% of liver offboarding occurs during daylight hours, while 77% of liver onboarding occurs during off-hours.

*These data include only organs that were transplanted and does not include organs that were declined during the NMP process. Anecdotally these discarded livers occur in a similar time pattern.